Thursday, July 31, 2014

Vacation Day from Summer

Here it is, the very last day of July, in the normally hot, arid southwestern cities of Fort Worth and Dallas, Texas.

And the temperature is about 75 degrees.

At 2:00pm.

Now, where you live, having a temperature of 75 degrees at 2:00pm may not be significant. But here in north Texas, this is downright amazing. It's wonderful! It's refreshing and invigorating.

It's also rare. It's like a vacation day from summer.

To put this in context, consider that the average low temperature for this date is 76 degrees. And that low temperature would occur at around two in the morning, not two in the afternoon! Meanwhile, our average high today should be 97. And the record high has gotten up to 106 on this date.

But not today!

Today, we have overcast skies, a bit of humidity, but some gloriously cool air! This is more like a typical summer day in, say, Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, which is situated at the mouth of New York Harbor. Or maybe mid-coast Maine, where my Mom grew up, and where our family used to take summer vacations.

When I lived in Brooklyn after college, this is the type of day I'd choose to walk down to Bay Ridge, a neighborhood in the southwestern corner of the borough. I liked to hike along streets lined by big homes and towering trees in that tidy, quiet, upper-middle-class enclave, and escape the congestion, noise, and dirtiness of the rest of the city. The breeze would come up from the Atlantic Ocean, fresh and clean. Today, I'm not sure how clean our air is here in north Texas, but it can't be as dirty as it otherwise would be if it was blazing hot, with hardly any more breeze than when somebody sneezes.

In Maine, the rugged natives who live in the Pine Tree State would be complaining about the 70-degree heat on a day like today, but down by the shore, or on a pier, if the wind was strong enough off of the water, I'd probably be wearing a light jacket. Of course, when the sun shines in Maine, just like anyplace else, the temperature can get rather uncomfortable. But at least things cool off at night up there, whereas here in Texas, temperatures can remain in the 90's well after sunset.

How nice to know we won't have that problem this evening! Indeed, this morning, it was weird to walk around outside in shorts and feel a tinge of a chill in the breeze. I pulled some weeds in the backyard, and didn't perspire at all! This afternoon, I went out in my car to run some errands with my windows rolled down and my sunroof open - and after I finished my errands, I drove around for another half an hour, enjoying the sheer luxury of being a little chilly on a summer afternoon with all the windows rolled down! The leaves in our trees are rustling in the breeze, and it's not the raspy rustling of dry, dying leaves that typically have begun to fade in Texas' brutal summer heat. In fact, things have been so mild all season, in comparison to our normal summers, that the trees still have bright green leaves, and the grass is still bright green as well. We've no leaves dulled by hanging in incessantly hot air, or sprawling yellow patches of parched lawns, where the grass has decided it can't compete with the sun.

At least, not yet.

Sure, here in north Texas, we still have the worst of our usual summertime heat to come. August and September can drain the chlorophyll out of the hardiest Texas plants, just as it can drain the energy out of the hardiest Texan.

At the end of July, in both Maine and New York, the locals will be starting to lament the passage of summer, a season that goes all too quickly in their parts of our world. Yet here in Texas, days like today are only a cause for lament because we know they won't last - the heat will return, and sooner than we'd like. Up north, they feel deprived by cloudy days in their summers, but here in Texas, cloudy days are a gift - especially when they keep temperatures so far below normal.

Summer won't end for us until sometime during the first couple of weeks in October. All the more reason to soak up days like today.

It's not that the daily weather forecast should hold so much sway over how we feel, or our outlook on the day - but it usually does, doesn't it? Below-average summer temperatures are enthusiastically welcomed by many Texans, just as above-average winter temperatures are usually welcomed by people up north. Considering how much of our days we spend inside, and how little time we actually spend outdoors, why should the weather, temperatures, and precipitation matter so much to us? Lots of office workers don't even get to sit near an exterior window during their workdays. Yet nice weather is quite important to most of us. Even when we don't get to enjoy it. Even when it's as accessible as being on the opposite side of a wall near you.

I haven't gotten to spend a lot of time outdoors today, but what time I have been able to spent outside, I've thoroughly enjoyed. Maybe that's why good weather is important to us, even when we can't drop everything else and enjoy it to its fullest.

Just like today in north Texas, a little bit of enjoyable weather is better than none at all!

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Dementia Doesn't Let Us Forget

My Dad is reading today's newspaper for the third time. The third time - today.

Usually, he only reads the newspaper twice a day.

After six years of senile dementia, the number of times he reads each day's newspaper isn't strange to my Mom and me.

But it's still sad.

Not as sad as last night, however, when yet again, we figured out that he didn't know he has another son. This happens regularly. When we told him the name of his other son, Dad didn't know where he lived, or that he's been married for over 20 years. Or that he and his wife have five children.

His jaw always drops when we tell him about his five grandchildren. It dropped again last night. Mom is usually the one who sits down with Dad and some photographs, and goes over our relatively small family tree. And whenever she gets to the part about his five grandchildren, his reaction is always the same.

Dad's sister moved from Brooklyn to Florida a couple of years ago, but Dad still tries to call her apartment in New York. Sometimes, he ends up reaching a telephone operator there, which makes him begin to worry that something bad has happened to his sister.

What else can't he remember? Well, he doesn't know his right from his left. He can't remember what month we're in, or which kitchen drawer holds our everyday silverware. He can't remember where he and Mom, for over a decade, have attended church.

He used to have hobbies, like gardening, painting with watercolor, crossword puzzles, and jigsaw puzzles. Now, he either has zero interest in them, or simply can't process how to do them. His paintings hang throughout our house, but he thinks he only painted the biggest one.

His mobility has declined significantly after a fall last month, and when a friend from my parents' church brought over a walker to help him get around, Dad couldn't figure out how to use it.

But he can usually remember our street address and ZIP code. Due to his fondness for ice cream, he has already learned to ask for Klondike ice cream bars, which Mom bought for the first time on a whim over this past Fourth of July weekend. He also has a couple of Bible verses he can recite with remarkable accuracy, including his favorite, Isaiah 41:10.

He can still dress himself, brush his teeth, and accomplish most of the steps in preparing his lunchtime ham-and-cheese-on-a-bagel sandwich. He usually remembers who Mom and I are, and even occasionally, the names of a couple of our long-time neighbors.

His physical therapist rates his dementia as "mild," in comparison with her other patients, but that's little comfort to Mom and me. All things considered, we still know we have things easy, at least as far as not having to deal with all of the additional burdens Alzheimer's brings. Dad's neurologist continues to insist that Dad does not have Alzheimer's, and for that, we are grateful. But knowing we have it easy, compared with other families, still doesn't make it easy.

I chatted with a couple of fellow choir members at my church last week who are caring for their elderly parents with similar problems, and we all agreed that until this whole responsibility of elder care entered our lives, we had no idea what it involved.

"You know what drives me nuts?" one of the women laughed. "When people tell you, 'Be sure to take care of yourself. Be sure to take some time off. Go on a vacation to get away from things!'"

"Yeah, right," another woman lamented. "Take care of yourself? When? Take time off? And spend that whole time worrying about your parents? Besides, you notice how other people who say this stuff always offer to step in and take over your parents' care so you can take that vacation!"

Another friend recommended a book about caring for people with dementia, and the author of that book tried to make a convincing argument for adult day care, saying that it's good for people with dementia to get out of the house and into an environment with their peers. But that makes little sense to me. After all, the whole point of dementia is memory loss - particularly short-term memory. Dad already doesn't like to leave the house for any reason. His horrible memory gets him anxious and agitated easily enough already, thank you! It's bad enough trying to get him to attend church, an activity upon which he used to insist. Why bother tormenting him with an experience with a bunch of strangers at an adult day care he can't understand or whose benefits - whatever they may be - he can't appreciate?

Earlier this year, Dad's neurologist wanted to do a brain scan on him, and a nurse came to the house to attach electrodes to his scalp with surgical glue. They were going to record his brain activity at home for three days and then analyze it.

To the electrodes, the nurse attached wires that coiled down his neck into a battery pack. The whole process took over an hour. Dad kept asking what she was doing, and the nurse would patiently explain to him about the brain scan each time.

After she left, however, Dad couldn't remember she'd just been working on him, and he blamed Mom for trying to pull some sadistic joke on him. He was almost crying, he was so frustrated, not being able to remember what all of these nodes were doing glued to his head, and the battery pack dangling from his back. Before the next hour was out, he had ripped every one of those electrodes off of his scalp - along with some of his hair, and some skin. And frankly, Mom and I couldn't blame him.

There are many things in life upon which I consider myself as qualified as anybody else to comment. And then there are other areas of life where I realize my opinions hold very little weight, and I shouldn't expect them to. Parenting is one of those areas, and how to be a good spouse is another. Sports. Molecular biology. The movies.

Meanwhile, although I didn't ask for it, don't want it, and certainly don't enjoy it, I'm acquiring quite an insight into elder care and dementia care. One of my friends says I should write about this experience more than I do, but I find that doing so is difficult, because it's so personal for me - in a negative way. Besides, I want to respect my father's privacy, and wonder what he'd think about me telling his story online, if only he understood about blogging and the Internet.

I also understand, however, that dementia is one of those topics where helping other people see what it's like may help expand our society's dialog in relation to it.

I'm no expert on dementia care, and I don't want to have to be. Part of me also continues to resent God for putting my family in this situation to begin with, which means I'm still struggling with accepting what God has allowed, which means I'm no paragon of virtue or faith. And even though Dad has had this condition for a number of years now, Mom and I still can be caught off-guard by some of the ways it manifests itself. Oftentimes, I wonder if we're learning much of anything!

Yet we're thankful that things aren't worse. We're thankful that so far, we've been able to care for Dad at home. We're thankful for doctors and clinicians who seem to be quite competent, and who give us good direction for Dad's care. And we're thankful he's still with us, even though large chunks of his memory aren't.

He spends a good portion of his days reading his Bible, and we can't think of a better way for him to be using his time. Although God tells us that His Word is "profitable" to its readers, we're not sure how much of the Bible he's actually reading, comprehending, and retaining. We suspect he's re-reading the same portions over and over again, since he might not remember having already read them recently.

After all, he can't remember having read the day's paper an hour later.

Nevertheless, Dad still remembers that he's a child of God's. And that's something I need to remember through all of this, too.

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Does Happiness Have a Cajun Drawl?

Are you happy?

Chances are, your happiness depends on where you live.

At least, that's what a Harvard professor and his colleagues claim. They've analyzed some data from the Centers for Disease Control to chart, by city, the places where Americans are the happiest.

Generally speaking, according to this study, people who live in and around the San Francisco Bay area tend to be the least happy, along with people living around Seattle, Chicago, Indianapolis, Detroit, and from Boston all the way down to Washington, DC. Alternatively, residents of Montana, Arizona, Texas, and the deep South tend to be the most happy. Along with a pretty good chunk of Delaware.

Of course, happiness is a profoundly relative concept, isn't it? "Happiness" is a mixture of contentment, satisfaction, ease, peace, and harmony, at least in proportion to what we know, expect, and experience. Our happiness is also affected by our personality and our health. And to a significant degree, we evaluate whether we should be happy by pegging ourselves against the people we consider to be our peers, or with whom we want to be associated.

Throughout all of this, our faith plays a core role in how we view our life, our circumstances, our relationships, our aspirations, and the things in which we place our trust and upon which we peg our chances for inner peace. And we all have faith in something, whether it's in Jesus Christ, or Mohammad, or ourselves.

Not that this particular happiness study is trying to prove that geography is more important than anything else in how happy we are - or aren't - but it is an interesting snapshot of where we Americans tend to be the most content, and where life apparently is best lived.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, the New York metropolitan region ranked dead last in terms of its happiness quotient. It's the most densely populated region of the country, with some of America's highest taxes, housing costs, and insurance rates. Normal daily work commutes can stretch into two hours one way, competition for employment is fierce, and political corruption is a way of life. Sure, it's a spectacular place to visit, but even though they may live cosmopolitan lives there, few New Yorkers truly derive deep satisfaction in doing so.

On the other hand, it's surprising to learn that one state holds the top five metropolitan areas with the greatest proportions of happy people. It's Louisiana, a state more often associated - especially by New Yorkers - with rural, backwater rednecks and a simplistic way of life. Then again, consider the cable TV show Duck Dynasty, proudly filmed on location in Louisiana's infamous swamps. The show's mantra is "happy, happy, happy," so maybe there's something to it.

And of these top five cities from Louisiana, not one of them is New Orleans. The number one metro area is Lafayette, covering two parishes (or counties), with less than half a million people in the city and its suburbs. The city's main attraction appears to be an exceptionally low unemployment rate of 3.3% in Lafayette proper, which by itself likely accounts for a significant amount of its residents' happiness. It's a generally conservative place politically, and its economy is based mostly on blue-collar and service industries.

Lafayette does have a symphony orchestra, a regional airport, several colleges, and a couple of museums, but nothing prestigious enough for any of us to have ever heard of - unless we'd lived there before.

The other four cities from Louisiana that top this happiness list are all similarly unremarkable. Unless, however, you consider how remarkable it is that such unglamorous, unexciting, unsophisticated, and relatively unknown cities can claim the top five spots for being full of so many happy people.

Of the top ten on this list, nine are Southern cities, with Nashville being the largest of the lot, and the most famous. The one northern city is Rochester, Minnesota, which is home to the highly-regarded Mayo Clinic, as well as a major facility for IBM. Minnesota is known for its brutal winters, so balmy weather obviously isn't a major priority for Rochesterites, most of whom must be pretty well-educated to work for employers like the Mayo Clinic and IBM.

And as far as big cities are concerned, Nashville has grown so much over the years, its traffic congestion can rival anybody's, and its Tennessee summers can be downright sweltering. It is, of course, a dominant player in the music industry, but it's also got bragging rights as a prestigious college town, and it's home to Hospital Corporation of America, the largest operator of healthcare facilities in the world.

So what does all of this mean in terms of how legitimate "happiness" is? We've got the "happy, happy, happy" bubbas down in Louisiana, and it would be easy for coastal sophisticates to write them off as a bunch of simpletons too swaddled by southern breezes and Cajun jambalaya to know how much better life can be beyond their mossy bayous. But in stark contrast to Louisiana, Rochester and Nashville boast world-class corporate and cultural features with which the stereotypical bayou city can't compete.

Of course, the stereotypical Louisiana bubba likely wouldn't want to compete for jobs in Rochester and concert tickets in Nashville anyway. Which probably helps explain why they're so happy. If Duck Dynasty is any guide, they don't even mind being called "bubbas," either, since to many of them, being one is a point of pride, not derision.

Hey - they're not the ones commuting to jobs that stress them out and pay just enough to cover atrocious rents and income taxes. Louisianans don't go to sleep every night to the lullaby of ambulance sirens and utility company jackhammers. Not outside of New Orleans, anyway. Nobody in Lafayette has to stuff themself into an aluminum tin can and rocket through underground subway tunnels with the smell of somebody else's urine turning their stomach. If anybody in Louisiana wants to subject themself to an assault on their senses, they can visit New York City as a tourist, soak up the bedlam, and then return home, happy that they don't have to put up with that chaos on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, people from all over the world continue to stream onto Manhattan Island, and spill over into the boroughs, thinking that Gotham is where they can find true happiness. Sexual happiness, economic happiness, artistic happiness, cultural happiness, political happiness... when all the while, where they probably should be going is likely more mundane than the hometowns they've left.

So, is true happiness found in the ordinary? In the unexceptional, uncrowded, and inexpensive? Do skyscrapers, an aging mass transit system, historic bridges, ultra-liberal politics, and 24/7 congestion result in happiness? Or do the people who willingly subject themselves to such things their own worst enemy for figuring that's the price they pay for some sort of urbane significance? Are they a lot of realists, and cynics, who compete with each other to be the best at whatever jobs they're doing, but who also know that onerous rents will only continue to rise until dangerous crime also rises - one of the city's more perverse balancing acts between boom and bust?

No, New Yorkers aren't very happy people. It appears that most urbanites across the United States are not. But they'd probably be even more miserable if they had to live in Louisiana.

Which likely makes Louisiana's bubbas even happier, knowing they won't have to share their idyll with all 'em obnoxious city slickers!

Friday, July 11, 2014

Armor and the Night Watchman

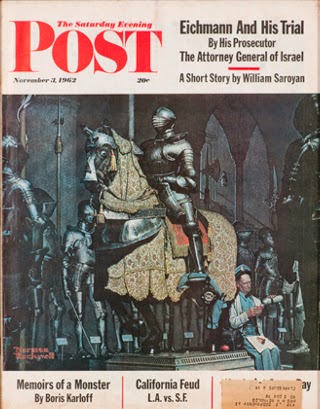

|

| "Lunch Break with a Knight" by Norman Rockwell, 1962 |

An early clue that I wouldn't survive architecture school came when one of my studio professors scoffed at the skills of populist painter Norman Rockwell.

"That's not art," this particular professor bellowed to us second-year students perched on metal stools beside our white drafting tables. Rockwell wasn't a good artist, supposedly, because he was too literal. Good art, according to our professor, should be different things to different people.

Reality is relative, right?

Sure, I thought; sometimes art can be interpreted in multiple ways, and sometimes maybe not. But do presumptions of the latter mean Rockwell was a bad artist? Not in my book.

This was one of the many disagreements I had with how my architecture professors wanted their students to view the profession, and our world in general. Suffice it to say that I never obtained a degree in design.

As far as Norman Rockwell is concerned, however, I'm not sure how anybody can argue that his art isn't compelling. Take, for example, what's probably my favorite Rockwell work, "Lunch Break with a Knight". He created it for the November 3, 1962 edition of the Saturday Evening Post, a popular magazine in his day. And while at first glance, it looks like a literal depiction of a museum security guard having a break in a darkened gallery featuring suits of armor, there's a lot more going on that people like my architecture professor apparently miss.

The setting for this painting is attributed to the former Higgins Armory Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts, whose collection has since been assumed by the Worcester Art Museum. But we don't really need to know the setting from which this tableau has been adapted to understand that body armor has had a long and colorful history. And that the best armor was usually worn by the most powerful warriors. And that masculinity, for all of its pretense of aw-shucks simplicity, can be downright audacious in the gaudy spectacle some men make of themselves. Just look at all of the shiny metal that was worn into battle after being perforated with intricately-designed embellishments, polished, adorned with plumes, and strapped with leather and fabric.

Oh, the poor horses that had to carry those men, clanking about in iron suits that must have weighed a ton! And even some of the horses were sheathed in matching metal shields. Towards the latter part of the Middle Ages, some armies were actually breeding special horses that could remain exceptionally agile under such a burden.

And how majestic these horses and riders must have looked! How invincible they must have felt! These were the rock stars of their day; the men for whom damsels swooned, and to whom kings apportioned property. Heroes, conquerors, with the physical strength to carry all of this armor and be mobile enough to be able to protect themselves. Wimps like me couldn't possibly hope to find any greater satisfaction wearing such a get-up than standing up and not tipping over.

Eventually, as guns and bullets replaced arrows and swords, armor plating became ineffective. By the turn of the 18th Century, such armor had become more ceremonial than functional, and was used more by commanders and royalty to monitor battles, than by foot soldiers doing the actual fighting. By the time of America's Civil War, body armor had become so obsolete, neither the North nor the South provided any to their soldiers, although some desperate men on both sides are reported to have personally bought pieces of body armor for themselves. Interestingly, across the world in Japan, this was about the same time that body armor had its last gasp for Samurai warriors as well.

But all of that is ancient history, right? How does Rockwell's painting relate to us today? After all, good art is supposed to be trans-generational and cross-cultural, right?

Well, let's look at Rockwell's composition for this scene, shall we? We've got a darkened museum gallery, with one armored horse and rider illuminated in the middle, suggesting that the museum is closed for the day, with at least one spotlight left burning to help the watchman do his job. We also see this watchman's black, industrial-sized flashlight - there, in the pocket of his jacket, that he's carefully draped over the foot and stirrup of our gallant suit of armor, and the finely clothed horse.

The watchman's cap is tilted back, presumably after he's rubbed his forehead in a relaxing gesture to indicate that all is currently right with his world. He's got his black metal lunchbox at his side, and he's seated on the display, comfortable and cozy. His napkin is neatly unfolded into a perfect square on his lap, and - instead of his healthy apple! - he's got a delectable slice of chocolate-frosted cake. We can almost taste what he's getting ready to enjoy with a steaming cup of coffee from his Thermos!

Okay - so it's a pretty typical depiction of a normal, working man's coffee break. Which is precisely the juxtaposition Rockwell wants to portray against the backdrop of such armored grandeur. Imagine the mortal battles through which all of this majestic armor has endured! How about the mighty men of valor who won wars - or lost their lives - wearing all of this hardware? Can you hear the noise and chaos of conflict, with clanging swords, stomping horses; the screaming and yelling of strong, muscular men fighting to the death?

Meanwhile, our docile watchman doesn't appear to have a weapon of any kind, unless you count that hefty-looking flashlight. He's got no gun, or bullet-proof vest, and why should he? What's in this museum that's worth his life? Everything is either insured, or so famous that nobody could steal it and hope to sell it on the black market. This man's presence in this closed, dark museum is more of a deterrent for bumbling vandals or mischievous teenagers than a front line against a desperate aggressor.

And what of all these suits of armor, anyway? Sure, we see little placards at the feet of every display, where museum officials have provided some information about who might have worn each particular piece, or when it was used. But who among us would otherwise know that information, or the names of the men who lived and died in these suits? In their day, they were men of value, importance, intrigue, and prestige. But today? We look at their armor and briefly marvel at how primitive warfare used to be. Today, our state-of-the-art Kevlar and other sophisticated, high-tech fabrics that serve as modern body armor function amazingly well, even if they don't look as grand as these suits of armor.

Indeed, it's the irony between grandeur and humility that embodies Rockwell's message with this painting. Grandeur of the past, and forgotten names, contrasted with the humility of a night watchman, taking his coffee break, and a brief, relaxing respite at the feet of armor that once stood between life and death for the person wearing it. And speaking of feet, a full graphic of this painting shows that the watchman is a rather short fellow, seated on the pedestal with his feet dangling up off of the floor. Not exactly swashbuckling, right?

Okay. So... here's where Rockwell's painting hits home. Four hundred years from now, who's going to remember your name? How antiquated is what you're wearing right now going to look? How significant will what you're doing right now for a living have been, even if you're saving some current entity from defeat?

Maybe people who don't think such paintings are art simply don't like what such paintings are saying.

Thursday, July 3, 2014

Independence on Parade

When I was a kid, the little village in which we lived threw a Fourth of July parade.

It was a small parade, with not a lot of excitement, but our humble village in Upstate New York was small and boring, too. So it kinda fit.

We had a volunteer fire department, and they'd ride their big red trucks through town on the evening of July 4. Local owners of old cars would line up and drive them through town, too. And people on the fire trucks and the old cars would throw candy and trinkets to us kids who lined the two short blocks of the parade route.

Beforehand, back at home, Mom and Dad would give us our nightly baths, and then take my brother and me, all squeaky clean in our PJs, down to the village, where we'd sit in the heat and humidity of Central New York's steamy summers, without air conditioning, in those Volkswagen buses my parents used to own.

Our father's mother and sister would usually be up from Brooklyn, taking a break from the chaos of a typical New York City July Fourth, but I can't remember them joining us at our kitschy local parades. Coming from the big city, they probably didn't think it was worth the bother.

It's an American tradition, isn't it? The Fourth of July parade. Here in Arlington, Texas, we have one of the largest such parades in the country, although I don't usually attend. Julys in Texas are usually beastly hot, even in the mornings, beating anything we had in Upstate New York. And mornings are when Arlington's annual parade is held, because it's still cooler than the afternoon, or even the evening. But that's not saying much.

One year, a friend of Mom's was the honorary grand marshal, meaning she got to ride in a vintage convertible at the head of the parade, and she just about suffered heatstroke from the ride.

New York City doesn't have an Independence Day parade, but that may be because practically the entire city succumbs to anarchy when evening comes, and all the illegal fireworks come out. Honestly, it sounds like the Big Apple is under attack, as bombs passing for pyrotechnics are detonated on any flat surface New Yorkers can find. It's awful; I simply cannot understand what is enjoyable about it. One year when I lived there, two people in Brooklyn's Bay Ridge neighborhood were killed when a rocket screeched up into the eaves of their wood-frame home, where it smoldered undetected for a few hours, until it suddenly consumed the roof, which then collapsed.

My favorite Independence Day memories, however, are more recent, and come from coastal Maine, and another Brooklyn. Only this one is spelled "Brooklin".

Brooklin is about the size of our old village in Upstate New York, and it has a parade, too, consisting of little more than fire trucks from local volunteer fire departments, and locally-sourced antique cars. But frankly, there are a lot of wealthy summer people "from away" who populate coastal Maine on July 4, and their antique cars are pretty classy, pretty old, and a lot more fun for me to admire now than when I was a kid.

Near Brooklin, at least as the crow flies, is an island called Deer Isle, and one of the villages on that island holds an annual fireworks display that, at least by small-town standards, is fairly respectable. There's something about fireworks going off above inky-black water that makes them more interesting to me. Maybe it's the reflection of all the lights and colors on the rippling surface of the water below.

Fourth of July is pretty much a kids' holiday, isn't it? Like Christmas. Most of the people launching their earth-shaking pyrotechnics in New York City are kids - or adults acting like kids. Meanwhile, the official fireworks shows most sensible cities put on every year can bring out the kid in a lot of adult spectators. Even in Brooklin today, candy and trinkets are tossed to the children lining the village's two-block parade route.

Ironically, though, driving through Deer Isle a few Fourths ago, on our way to a hillside viewing position for the fireworks show, my brother pointed out a newly-remodeled home owned by summer people from away. And you can tell the difference between homes owned by summer people and those owned by native, local Mainers. This home's lawn was covered by rented folding chairs and tables with white tablecloths, while tuxedoed caterers set out platters of food amongst candlelit hurricane globes for some fancy al fresco Fourth feast. Within view of the fireworks, of course.

Leave it to the one percenters to make their guests dress for dinner on Independence Day! In rural Maine, no less. While the rest of us dine on barbecued hot dogs and hamburgers in our shorts and flip-flops. And sweaty kids drizzle melted ice cream down their chins.

Ahh, yes. To each his own on Independence Day, right?

Tuesday, July 1, 2014

Twelve Staples Later

We're not sure how he fell.

But there he was, at the foot of the steps leading up to our wide patio door, splayed across the concrete, his little transistor radio in a couple of pieces a few feet away, and his eyeglasses another few feet further away.

I rushed down the four concrete steps to his side, quickly maneuvering to his head, telling him not to move. Mom was on the phone, calling 911. I think I prayed, but frankly, I can't remember.

It was Sunday afternoon, about a quarter to four, this past weekend. The temperature was in the mid-90's, but on the concrete, it felt like we were being baked alive. A giant magnolia tree towers over one side of our patio, but it's the north side, which is of no use in blocking Texas' incessant sunlight. Dad complained that the concrete was too hot, and even though he was wearing pants, it felt like his legs were burning.

Okay, he can feel his legs, I had the presence of mind to realize. That means he's probably not paralyzed.

I told him to lay still, but he started moving his legs anyway. Okay, he's stubborn, but he's not paralyzed, I told myself.

Then the blood began to spurt from underneath his head. Mom came to the sliding glass door, a phone in her hand. "He's bleeding profusely!" I yelled. "A lot of blood!"

Mom got a towel from the nearby kitchen and tossed it to me. How long had she been on that phone with 911? I didn't hear any sirens. I wrapped the yellow hand towel around Dad's head. It quickly turned red.

"Keep talking to him," Mom instructed from the patio door, relaying what the 911 operator was telling her.

"Dad, you'll be OK," I said grimly, not sure to believe it myself. No grand theology, no deep thoughts, no insightful advice. But now I remember praying to myself. "Please, Lord, keep Dad OK."

I had been fearing such a moment for a couple of years. I'd even been researching contractors and getting quotes on having a handrail installed on the patio steps. And now it was actually happening. Was this it? The end? For some reason, I didn't think so.

Finally - after what everybody else in these types of situations says seems like an eternity - I could hear sirens. And soon, the banging of aluminum doors on the other side of the house, and I could smell diesel fumes. Clomping through the side yard came a herd of young men: blue-suited EMTs from the ambulance, mixed with tall guys in yellow overalls from the fire department. They swooped in and took over, like it was all in a day's work... which, for them, it was.

A pneumatic stretcher appeared, along with a long, blue flat board. A neck brace, straps; the men worked methodically, yet with gentleness. They spoke calmly, efficiently, asking Dad questions in such normal voices that he, being hard of hearing, sometimes couldn't make out what they were saying. Before long, they had Dad strapped to the flat board, which was then strapped to the big, yellow stretcher, and they were taking him back around the side yard, to the waiting ambulance.

I think Dad spent more time in the back of that ambulance, idling by the curb as they prepped him for transport and communicated with the hospital, than he did actually laying on the concrete. Mom sat in the ambulance cab, and the firemen stood inside their truck, taking off their bulky, fire-retardant overalls. I didn't even hear the fire truck pull away.

We spent over six hours in Arlington (TX) Memorial Hospital's sprawling Emergency department, huddled in our own private room off of the department's main hallway. Since Dad arrived by ambulance with a head injury, the only delay we had was while an orderly quickly finished cleaning and clearing the small room from its last patient. Mom and I never had to sit out in the waiting room, although after a while, I began to wonder if the chairs out there were any more comfortable than the thinly-cushioned ones in our little private room.

Nurse after nurse paraded through Dad's room, attaching some medical things onto him, but mostly typing information into their computers. Dad's head kept bleeding - dripping - for several hours; a small pile of red, sticky gauze pads accumulated on the floor, along with drops of blood. But none of the medical professionals seemed to care; afterwards, Mom and I wondered if they wanted to see how much - and for how long - Dad would bleed. A neighbor who's a nurse has told us that with head wounds, as long as it's not a steady gushing of blood, bleeding can actually be good for the brain. It can help prevent fluid-buildup under the skull.

When the ER doctor first examined Dad, he was all-business and quite serious. His words were few and clipped. He ordered a battery of CAT scans, and tests to be run on the blood a nurse would take from his vein. I thought about helpfully picking up one of the gauze pads on the floor and offering it to the nurse as a blood sample, but figured that would be a tacky thing to do, all things considered.

Honestly, she took four or five vials of blood out of Dad's arm. They certainly weren't worried about his losing any blood pressure!

My father is in his sixth year of dementia, and everybody who came into the room was treated to his exhibition of his left arm, which has a scar from a childhood accident back when he lived in Brooklyn. Repeat visitors to his room were treated to the same exhibit, since Dad didn't remember they'd already seen it, and had already given the appropriate "oohs" and "ahhs" over it. "I got that from a broken soda bottle some kid threw at me," Dad would proudly proclaim, every time.

Dad is a veteran of bad injuries. That's what he wanted to tell everyone.

And he survived this injury, too - complete with twelve staples administered by the ER doctor, who returned to the room with an amazed grin on his face. "You officially have a thick skull," he proclaimed to Dad with a flourish.

The doctor apologized for the wait, but he'd sent somebody out to Home Depot to replace their stock of staplers. And with that, he produced a fairly generic-looking stapler inside a sealed plastic bag, but the joke was lost on Dad. "I'm not getting stitches?" Dad actually sounded disappointed upon learning staples would do the job better.

As we waited for the last batch of tests to come back, and the nurses had left the room, Dad began to get restless. "Can't we just get up and leave?" he'd ask, despite his right arm and left hand still being hooked up to monitors.

Because of his dementia, he kept forgetting that he was in the hospital. He completely forgot his fall, or the gash in his head, or the blood, or the ambulance ride. Even today, he remembers none of it. While we waited in the Emergency department, Mom and I kept telling him what had happened, why he was in the hospital, and why we needed to wait for the doctor's "all-clear" before we could leave. And every time we told him he'd fallen, and about the firemen and the ambulance, and the 12 staples holding his scalp together, he'd look at us with surprise and amazement. If it wasn't for the equipment still monitoring his vital statistics, he'd likely not have believed us. He kept saying he felt fine.

Which, he probably did. Dad has always had a high pain threshold. One time, years ago, he walked around with a broken toe for a week before its incessant swelling finally convinced him to listen to Mom, and see his doctor.

In the rush to get him to the hospital, we'd left a pool of his blood back on the patio, and by yesterday, it had turned black. We kept pointing out the spot to him, trying to see if we could jog his memory, but nope: He'd look at us in surprise and amazement as we re-told the story of this past Sunday afternoon.

Finally, sometime today, when I asked him about the spot - that I've since washed away, leaving a faint stain - he remembered that it was his blood, from when he fell. But the ER visit? That's something senility apparently has removed from his consciousness. Along with the reason he fell in the first place.

He fell backward, climbing up a short flight of steps. Usually, when somebody stumbles while going up stairs, they fall face-forward, onto their knees or face. Why did Dad fall backwards, and land about three feet away from the bottom step?

Back in the 1970's, his mother - who also suffered from dementia - had an aneurysm. It happened while she was walking up to the third-floor landing of the Brooklyn apartment she shared with Dad's sister. Without a sound, or ever crying out in surprise, my grandmother fell backwards, and slammed with a giant thud on the landing below.

It took my aunt about half an hour to find an ambulance company that would dare to enter her neighborhood, it had become such a dangerous place as white flight changed the entire city of New York. That was also in the days before our modern 911 dispatch systems. By the time an ambulance crew arrived, we learned later, my grandmother was dead, but because both the ambulance company and the hospital feared a lawsuit from my family, they transported my grandmother to the hospital and kept her on life support for several hours before officially pronouncing her dead. Eventually, they told my aunt that her mother likely died from a sudden aneurysm, which is why she never called out as she fell.

The eerie similarities between her death and Dad's fall kinda haunted me a little. But this time, God saw fit to preserve Dad, and restore him to us with 12 staples and some occasional dizziness. He's not even very sore from the multiple bruises that are on his backside and shoulders, from landing on the concrete. His eyeglasses didn't break, and Mom was amazed to discover that after soaking the shirt he'd been wearing in plain water, virtually all of the blood that had stained it came out.

So, we've still got Dad, his dementia, and the prospect of taking him to his primary care doctor next week to have those staples removed.

And Dad will probably be more animated over the scar in his left arm than anything else.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)